The English Roots of Liberalism: From Locke's Study to the Modern Left — and the Masonic Thread

The English Roots of Liberalism: From Locke's Study to the Modern Left — and the Masonic Thread

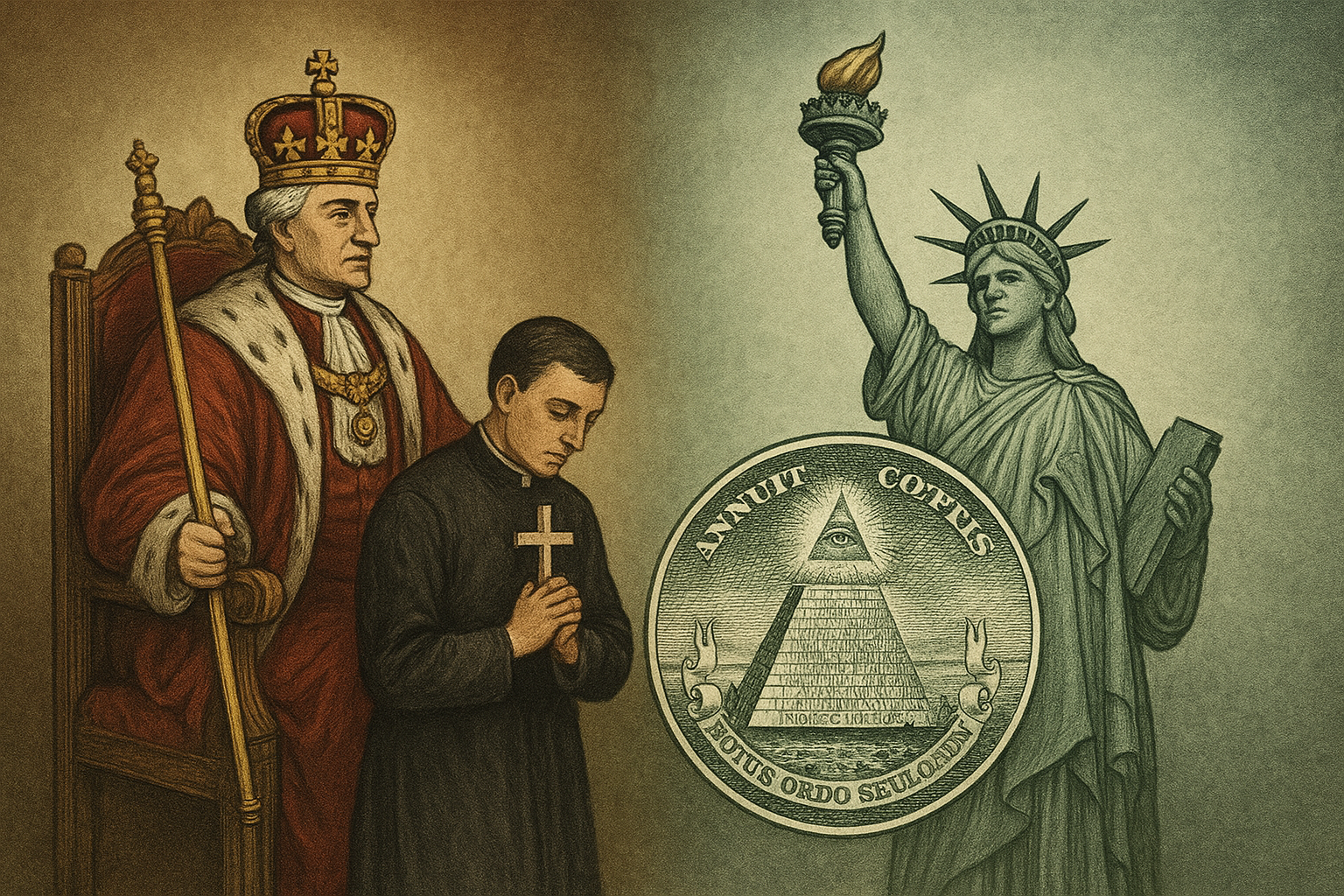

True enough. But dig one layer deeper and the trail leads straight to England — specifically to the coffee houses of London, the country estates of Whig aristocrats, and the smoky lodges of 18th-century Freemasons. What started as a very English quarrel over kings, taxes, and religious tests mutated over three centuries into the modern left-wing liberalism that now dominates universities, NGOs, and the Mexican progressive elite alike.

This is the story of that mutation — and of the Masonic network that helped carry the spark across the Atlantic and the Channel.

I. The English Incubator (1640–1720)

1. Civil War Sets the Stage

The English Civil War (1642–1651) was liberalism's violent baptism. Parliament executed a king (Charles I) for claiming divine-right absolutism. The Levellers — proto-libertarians in Cromwell's army — demanded votes for all freeborn Englishmen, an idea so radical it terrified even the victors.

2. Locke: The English DNA

John Locke (1632–1704) was the movement's first systematic philosopher. Exiled in the Netherlands after plotting against Charles II, he returned after the Glorious Revolution of 1688 — the bloodless coup that replaced Catholic James II with Protestant William & Mary under a Bill of Rights. Locke's Two Treatises of Government (1689) supplied the operating system:

- Government exists by consent.

- Rights to life, liberty, and property are inalienable.

- Rebellion is justified against tyrants.

All of it written in an English country house, funded by a Whig patron.

3. The Masonic Transmission Belt

Here enters Freemasonry. The first Grand Lodge was founded in London, 1717, uniting four existing lodges of stonemasons-turned-gentlemen. By 1723 it had a constitution written by James Anderson, a Presbyterian minister. The lodges became:

- Secular salons where Anglicans, Dissenters, and even Catholics debated ideas banned in public.

- Networks that spread Locke's pamphlets to Edinburgh, Dublin, and colonial port cities.

Voltaire was initiated in London in 1726; Benjamin Franklin joined in Philadelphia in 1731. The Masonic lodge was the 18th-century equivalent of a private Discord server — encrypted, cross-class, and transatlantic.

II. The 19th-Century Split: Two Liberalisms, One English Root

| Year | Event | Classical Liberal Outcome | Social Liberal Seed | |------|-------|--------------------------|---------------------| | 1776 | American Revolution | Jefferson's Declaration = Locke 2.0 | — | | 1789 | French Revolution | Masonic generals; Déclaration des droits | Terror discredits pure individualism | | 1832 | English Reform Act | Extends vote to middle class | Working-class agitation begins | | 1867 | Second Reform Act | Vote to urban workers | John Stuart Mill flips: now defends state education, women's suffrage |

Mill's pivot is the hinge. Early Mill (On Liberty, 1859) is peak classical liberalism. Late Mill (Chapters on Socialism, 1879) flirts with redistribution and workers' co-ops. The English soil that grew laissez-faire also nourished the welfare state.

III. The Masonic Echo in the 20th-Century Left

Freemasonry waned as a political force after 1900, but its cultural residue lingered:

- Secular universalism → modern human-rights language.

- Meritocratic brotherhood → progressive disdain for inherited privilege.

- Ritual tolerance → identity-politics coalitions.

The Fabian Society (1884), intellectual godfather of the British Labour Party, met in rooms once used by Masonic lodges. Sidney and Beatrice Webb weren't Masons, but they inherited the same Enlightenment confidence that rational elites could redesign society.

Across the ocean, Franklin D. Roosevelt's New Deal (1933) cited English progressive liberals like T.H. Green and L.T. Hobhouse. FDR himself was a 32nd-degree Mason.

IV. The Mexican Detour: Juárez, Masons, and Morena

In Mexico, Benito Juárez — a Zapotec orphan turned liberal president — was initiated into a Scottish Rite lodge in Oaxaca in 1847. The Reform Laws (1857–1860) were pure English liberalism via Masonic channels:

- Nationalize Church property (Locke's secularism).

- Civil marriage and cemeteries (anti-clericalism).

- Constitutional government (Glorious Revolution 2.0).

Fast-forward to 2025: Claudia Sheinbaum, Mexico's first female president, is a secular Jew with a PhD in energy engineering. She quotes Amartya Sen and Martha Nussbaum — heirs of Mill's social liberalism — while governing with a supermajority. The Masonic lodges are gone, but the English liberal genome persists in UNAM lecture halls and Morena's technocratic wing.

V. The Final Mutation: From "Leave Me Alone" to "Make Me Equal"

| Early English Liberalism | Modern Left-Wing Liberalism | |-------------------------|----------------------------| | Negative liberty (freedom from) | Positive liberty (freedom to) | | Property as sacred | Property as social construct | | Government as night-watchman | Government as equalizer | | Tolerance of difference | Celebration of difference | | English Bill of Rights (1689) | UN Declaration of Human Rights (1948) |

The same root, three centuries of grafting.

Conclusion: The English Ghost in the Progressive Machine

Next time a 25-year-old in Condesa or Brooklyn tweets that "liberalism = capitalism," remind them: capitalism's greatest critic, John Maynard Keynes, was an English liberal. So was the architect of the NHS, William Beveridge. So, in spirit, is the Mexican secretary who expands IMSS coverage.

The family tree is gnarled, but the trunk is unmistakably English — and yes, a few of its thickest branches grew in candlelit Masonic lodges where men in aprons first dared to imagine a world without kings or popes.

The revolution eats its children, but it still speaks with an Oxford accent.